Alison Matthews David (Ryerson University, Canada). Fearful/Fearsome Fashions: Crime, Clothing and Dressing to Harm and Protect in the Long Nineteenth Century

Visual, textual, and fi lmic representations of fear abound, but few scholars have examined the key role that dress and accessories play in the physical, social and psychological production of and protection from fear (Matthews David 2016, 244–267). Along with modesty and adornment, classic fashion sociologists like Veblen and Simmel have posited protection, including protection from social shame, as one of the three key functions of dress. Yet this function broke down, oft en literally, at specifi c times and places in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in response to population expansion, social dislocation and increasing anonymity in urban centres.

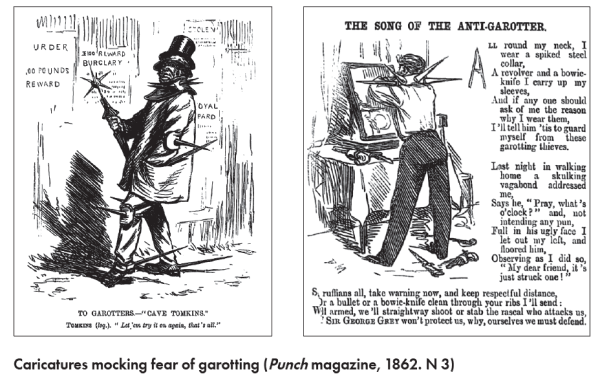

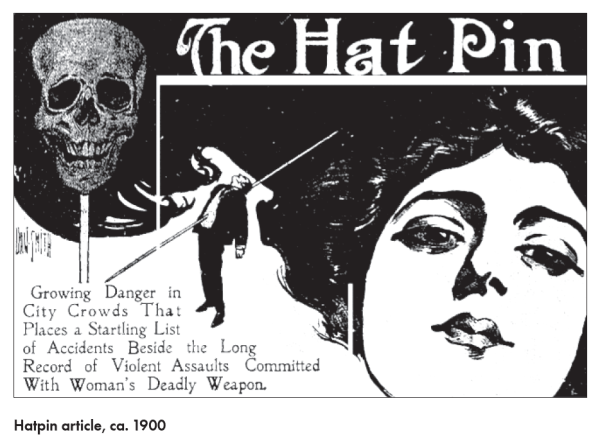

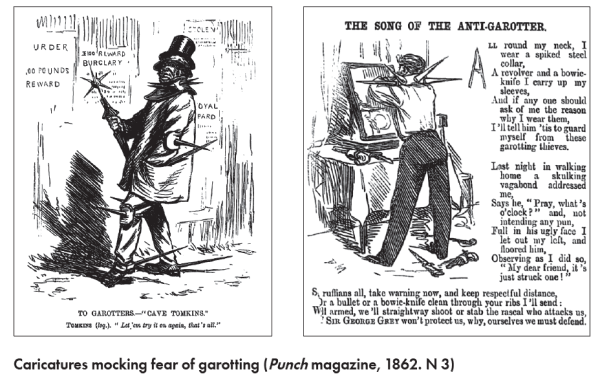

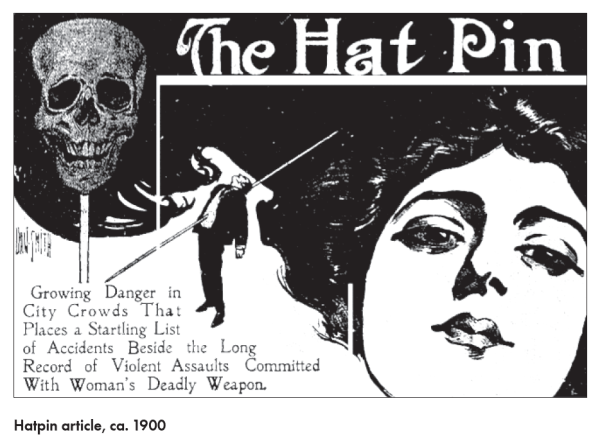

In the context of a major research project on the theme of clothing and crime, this paper focuses on two social registers of dress: that of fashionable bourgeois men and women, whose aim was to protect their persons against street crime, and the very different wardrobes of street criminals themselves, who were ingeniously using working-class dress and accessories to perpetrate attacks on people and property. In reaction to specific moral panics, like the “garrotting crisis” of the 1860s where middle class men were strangled for their pocketbooks, fearful bourgeois invented and adopted specific defensive accessories (Sindall 1990). These included “anti-garotting” cravats with spikes hidden behind silk neckties, deadly swords concealed in elegant canes and even a miniature belt-gun that could shoot the potential strangler standing behind you. Increasingly mobile women had their own stylish devices, including “dagger fans” and long jeweled hat pins to repel assailants who came too close to them on omnibuses or in other public spaces (Godfrey 2012). Gender stereotypes meant that middle class men who defended themselves were hailed as heroes, whereas women were feared as femmes fatales and violent assailants, as the man impaled on a hatpin in this newspaper image suggests.

By contrast with these fashionable protective strategies, street criminals from the working classes created fearsome weapons by adapting their own humble everyday garments. As actual trial transcripts, police accounts, and newspaper articles document, any banal item could be turned into a deadly weapon. These terrifying accessories included simple bandannas, handkerchiefs and leather belts used to silence or strangle, pointed shoes or heavy boots used to kick and maim, and even knitted socks could be stuffed with rocks to bludgeon enemies or targets. Working-class women could use their voluminous pockets to hide stolen items as well as gaudy or provocative forms of dress to sexually lure potential clients to spaces where they could be undressed, made vulnerable and robbed of their belongings. Unraveling complex class and gender dynamics and emotional, embodied responses to fearful and fearsome dress strategies in urban environments contributes to our understanding of broader narratives and representations of fear in society.

List of References:

Matthews David A. Blazing Ballet Girls and Flannelette Shrouds: Fabric, Fire, and Fear in the Long Nineteenth Century // Emotional Objects Special Issue of Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture. Bloomsbury, May 2016. 14:2. P. 244–267.

Sindall R. Street Violence in the Nineteenth Century: Media Panic or Real Danger? Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1990.

Godfrey E. Femininity, Crime, and Self-Defence in Victorian Literature and Society. New York: Palgrave- MacMillan, 2012.

In the context of a major research project on the theme of clothing and crime, this paper focuses on two social registers of dress: that of fashionable bourgeois men and women, whose aim was to protect their persons against street crime, and the very different wardrobes of street criminals themselves, who were ingeniously using working-class dress and accessories to perpetrate attacks on people and property. In reaction to specific moral panics, like the “garrotting crisis” of the 1860s where middle class men were strangled for their pocketbooks, fearful bourgeois invented and adopted specific defensive accessories (Sindall 1990). These included “anti-garotting” cravats with spikes hidden behind silk neckties, deadly swords concealed in elegant canes and even a miniature belt-gun that could shoot the potential strangler standing behind you. Increasingly mobile women had their own stylish devices, including “dagger fans” and long jeweled hat pins to repel assailants who came too close to them on omnibuses or in other public spaces (Godfrey 2012). Gender stereotypes meant that middle class men who defended themselves were hailed as heroes, whereas women were feared as femmes fatales and violent assailants, as the man impaled on a hatpin in this newspaper image suggests.

By contrast with these fashionable protective strategies, street criminals from the working classes created fearsome weapons by adapting their own humble everyday garments. As actual trial transcripts, police accounts, and newspaper articles document, any banal item could be turned into a deadly weapon. These terrifying accessories included simple bandannas, handkerchiefs and leather belts used to silence or strangle, pointed shoes or heavy boots used to kick and maim, and even knitted socks could be stuffed with rocks to bludgeon enemies or targets. Working-class women could use their voluminous pockets to hide stolen items as well as gaudy or provocative forms of dress to sexually lure potential clients to spaces where they could be undressed, made vulnerable and robbed of their belongings. Unraveling complex class and gender dynamics and emotional, embodied responses to fearful and fearsome dress strategies in urban environments contributes to our understanding of broader narratives and representations of fear in society.

List of References:

Matthews David A. Blazing Ballet Girls and Flannelette Shrouds: Fabric, Fire, and Fear in the Long Nineteenth Century // Emotional Objects Special Issue of Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture. Bloomsbury, May 2016. 14:2. P. 244–267.

Sindall R. Street Violence in the Nineteenth Century: Media Panic or Real Danger? Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1990.

Godfrey E. Femininity, Crime, and Self-Defence in Victorian Literature and Society. New York: Palgrave- MacMillan, 2012.